JACAR Newsletter

JACAR Newsletter Number 38

August 31, 2022

Special Feature

Interview with painter TSUE Taiyo

To date, the materials that the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) makes available have been used for historical background research for audio-visual and other works.

The painter TSUE Taiyo is approaching the creation of his works using a novel style. He has been reading historical documents available at JACAR and forming the inspiration for his works in the process. He then uses delicate strokes to paint on the canvas scenes from former Manchuria that perhaps his great-grandfather saw as someone who went there as one of the agricultural pioneer settlers.

In this issue, we will present some of the new possibilities for putting JACAR’s materials to use by asking Mr. Tsue about his process from the conception to the completion of a work, and showing how historical records have their payoff in a work of art such as painting.

PROFILE

TSUE Taiyo

Born 1996 in Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan.

Painter.

*Currently enrolled in the Oil Painting Technique and Material Department, Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts.

*Held solo exhibitions in 2018 at Gallery Mitake (Tokyo) and in 2019 at Ginza Gallery Stage-1 (Tokyo) and in 2021 at the Nihonbashi Takashimaya Department Store (Tokyo).

*In July 2022, held solo exhibition “Sora no Iro” at Gallery Mitake (Tokyo).

*Created the cover art for Kagohara Aki, Anata wa doko no iru no ka (Shunjusha, 2022), a novel depicting what lay ahead after World War II for former Manchuria’s “pioneer” settlers.

In 2019, when I was researching the history of my great-grandfather, who had been among the Manchuria and Mongolia settlers groups, an acquaintance of mine who worked for the National Shōwa Memorial Museum told me about JACAR.

At first, I had no idea how to look up anything. That’s how I got started. Initially, I looked for things by using the reference codes that I found listed in previous research. However, these days I look for materials by searching with keywords like personal names, institutions, and event names. “If I don’t get any results using this word, let’s see what happens if I change my search to that word,” I’d think, or if I got far too many results, I’d think, “Let’s change the search conditions and try to specify a time period.”

Little by little, I got the hang of it.

These days, I’ve been doing research about the people who were with the former Japanese Army’s special services. However, given that they were engaged in intelligence activities, very few items record any names. Keyword searches don’t produce many results even if you include names. In most cases, it only says “Head of the institution”. Accordingly, I make inferences based on points in time—i.e., “The head of the institution at this time was such-and-such a person, so this must be so-and-so”—to infer who individuals were.

This year, I’ve been thinking about painting something using the city of Hailar as my subject. There is a connection to the Nomonhan Incident of 1939 as well, as the 23rd Infantry Division was garrisoned there.

Before Covid-19 struck, I did fieldwork and got a sense of former Manchuria atmosphere while painting. However, with the strict infection control measures in place, I was unable to visit former Manchuria. When I was thinking of working methods that would replace going on location to gather information, I came across an album of photos from 1936 that were taken in Hailar. I wondered if I might still be able to create pieces based on the photos, records, and statements that were in the album even if I could not go there.

I thought this is what I found a bit interesting When I was looking for relevant historic records through JACAR.

It’s a report about how, at the suggestion of the Japanese Consulate, the Japanese army helped to deliver Christmas presents to Russians refugees who had escaped the 1917 Revolution in what was then Manchuria. The full report includes a list of the kinds and numbers of the presents, and even Russian-language receipts. From it, you can get a real sense of what things were like at the time.

The report also includes various notes, such as: “We’d like to give them presents which will demonstrate the high quality of Japanese products. However, if it’s something that is inferior to Western product, you’ll just have to give up and buy something at a Russian shop.” and “The Japanese toys were broken in shipping. Some may even break at the moment they’re handed over, so you must be sure to bring ones that are in good shape.”

I guess the Japanese military that were stationed here took the initiative of giving gift to Russians in order to win the trust of the locals. The records also indicate that close to 8,000 Russians fled here.

Yes. I had thought that there might not be any direct connections between it and the photo album, but as I leafed through the album I came to realize that in fact there might some small connections after all.

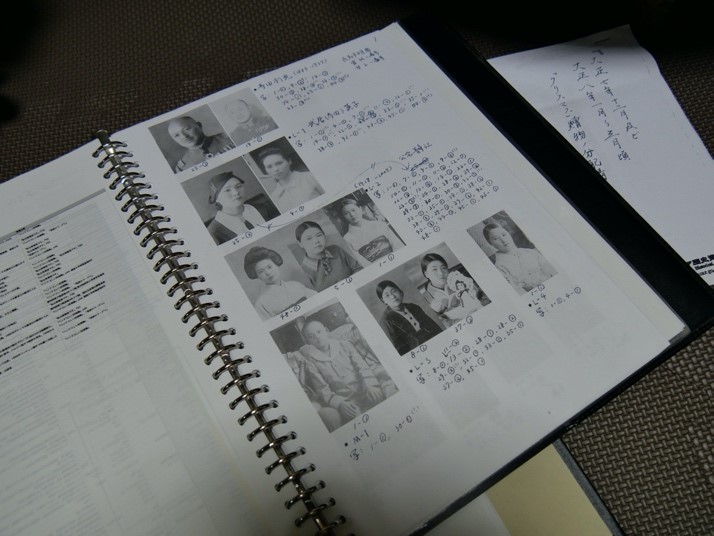

I got the photo album (Image 2) from ARYUNA Batueva, who is from Hailar and is an acquaintance of my wife who herself is from Inner Mongolia.Ms. Aryuna showed it to me as she was dividing up mementos of a deceased relative. I had mentioned to her that I was looking up things about former Manchuria, and she said, “I have a photo album” and showed it to me.

Ms. Aryuna also has roots among the Buryat-Mongolians who fled Buryat during the Russian Revolution. The photo album had been the property of ŌYAKE Shizue, who lived in Hailar from 1935 to 1937. She lived in Osaka after the war, and Aryuna met her while studying at Osaka University of Foreign Studies.

The various ethnic group of former Manchuria show up in the photo album, such as the Japanese advisor to the Northern Xing’an Security Forces, the family of a Chinese captain, and the leader of a Mongolian army unit. The advisor is TERADA Toshimitsu, who was known as the “father of Hailar” and was well known to people from all ethnic groups. Many photos of him remain, as well as photos taken at his official residence.

This photo was also taken at the Terada residence (Image 3). Ms. Ōyake is pictured among the “white émigré” Russians who attended a dance held there.

This photo was taken in 1936, the year of the Berlin Olympics. Given that everyone in the photo all seem to have been in their 20s, they may well have gotten the Christmas presents spoken of in the report I mentioned when they were children. Thinking about it this way, sometimes the materials I find do have some connection to what I create.

This is a Terada family photo (Image 4). You can surmise from it that his household employees included Russians and Chinese. You can catch glimpses of lives being led at the time in which people from various ethnic backgrounds including Mongolians, Russians, and Japanese were all interconnected.

Very few records about TERADA Toshimitsu remain today. However, we do know that after he graduated from the Mongol program at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages (predecessor to the present-day Tokyo University of Foreign Studies), he was posted as a military attaché. Beside this, we also know that he apparently served as a mediator in domestic conflicts for local residents where he was stationed. He seems to have been a sensible and gentle man.

There are also photos of his family and their household employees splashing about in a river. I have heard that he had a hard time being engaged in espionage activities for the army special services which was ruthless job.

I think Terada was an important figure in that he was the only person who could do the work he did. After he died, a bronze statue of him was erected in front of the main Hailar train station.

The original photo was quite grainy, so I have been unable to identify the people appearing in the photo. I made a list of the people who appear in the photo album (Image 5), and made inferences about who each person is. At this point, I think I’ve identified around 30 people. I can see that the more frequently someone shows up, the closer they were to the photo album’s owner.

When I assigned numbers to all the photos and then noted how many times someone appeared, in some cases I also figured out that a person who I thought was someone else was actually the same person but just in civilian clothes or a military uniform.

For example, this photo (Image 6) was taken around the time of the 1935 Halha-miao Incident (Battle of Khalkhyn Temple). It shows Japanese officers serving with the Japanese army as well as with the army of "Manchūkuo" along with their interpreters, all dressed in cold-weather clothing. The fourth person from the left in Image 6 is OKAMOTO Toshio, the man standing at left in Image 7.

It is extremely difficult to infer the names of people I’ve never heard about or of private persons whose names do not show up in public records.

I was able to identify this man (Image 8, on right) as Urzhin Garmaev, commander of the Northern Xing’an Security Forces. The commander was a Buryat-Mongolian, and in this photo (Image 9) we see what he looked like wearing traditional Mongolian clothing.

Terada and Garmaev were introduced to one another by a Russian sometime around 1927. While both men could speak Mongolian and Russian, they seem to have used Russian in their everyday conversations.

There are also photos taken of the pair with their families, which suggests there was mutual respect and trust between Terada and Garmaev.

Aside from Mongolian, Buryats also spoke Russian owing to their familiarity with Western culture. I understand that the Japanese believed that the bilingual Buryat, could be “useful”, and so warmly received the Buryat-Mongolians. Garmaev and his peers attended the Manzhouli conferences and participated in talks about national borders.

Mongolia at that time was at the mercy of Russia, China, and Japan. Outer Mongolia was being suppressed by the Soviet Union. While Inner Mongolia was officially Chinese territory, there were attempts by Mongolians to achieve independence or to try to link up work with Japan in some fashion. Hulunbuir, too, the setting of the album’s photos, saw two independence uprisings. The second of these movements was led by Merse (Chinese name: Guo Daofu). It ended in failure for lack of local support. After abandoning the independence attempt, Merse made a peace proposal to Fu Zuoyi.

When I looked through JACAR records about the history of this, I discovered that Colonel Terada played a mediating role by offering to serve as an intermediary with Fu.

Terada was in Hailar from around 1927, and South Manchuria Railway employees also engaged in intelligence activities. The name of “TERADA Toshimitsu” turns up (Image 10) in a 1928 report from the Harbin consul general sent by telegram to the foreign minister.

Also, it seems that when Terada was in Vladivostok, he was attached to the Russia section of the Imperial General Staff Office. An instruction given to Terada by the Army Minister in June 1928 (Image 11) clearly states that Terada is to “engage in intelligence work.”

Telegrams have also offered important clues. One 1928 telegram addressed to Terada (Image 12) indicates that the senders “want you to prepare a blanket after you pass through Hailar Station,” and there is correspondence from the unit to which he had been previously attached.

From the letters sent to him personally by his associates, too, I can get a sense of what conditions were like at the time and what his usual work activities were like.

This item (Image 13) is something that ARYUNA also showed me along with the photo album. It is a letter written by Terada on stationery for the Advisor’s Section of the Northern Xing’an Security Forces.

The letter was written on March 20, 1936. In 1935, Terada collpased from a stroke, and in 1936 he still suffered from the complication of paralysis on the right side of his body. Writing seems to have become very difficult for him, and this situation is mentioned in the letter itself. He apologized for not having written the letter by hand, and since he specifically mentioned that “Shizue-san has typed this” we know that Ōyake Shizue must have handled the typewriter for him.

Terada died from his illness in Hailar. On July 16, 1937. His rank at the time of his death was colonel in the army artillery (Image 14).

My way of using JACAR is different from academic research in that I focus on visual aspects. Even if you know when such-and-such an event happened, I’m wondering what the place was like where the event occcurred and what sorts of buildings were there. If we know what the month was, then what sorts of plants grow around that time? If I don’t know about things down to the details about minor accessores that were in daily use, then I can’t draw anything. What styles of clothing were popular at the time? Was this something brought in from Russia, or was it purchased on the streets of Hailar?

I’m not simply creating a story. I’m carefully investigating the facts, and taking care to not bring my own feelings into the work. If I bring in a fixed way of thinking into a work and allow it to trend off in one or another direction, I think it lessens the value of having made careful use of documents to create the painting in the first place.

During my sophomore year at university, I was given some Oshima Tsumugi [a type of silk fabric] which used to be owned by my great-grandfather. But the thing is, I never met my great-grandfather. I had heard that my great-grandfather was the captain of a transport vessel, and that he died in Okinawa around 1945.

This is not the same great-grandfather I mentioned before who had been among the “pioneer” settler groups. I wanted to know more about him, but I didn’t know how to do it and ended up finding almost none. My lack of research skills at the time had held me up, and in learning more about my settler great-grandfather I decided to make my investigations as extensive and as thorough as possible.

The fact that records are all connected with another in some fashion means that if you don’t look carefully at each and every one you wind up missing something. That’s why those instants when I discover a connection are interesting. “Oh, these records that I thought were of completely different genres are connected through that!”

Once I felt that I’ve managed to get hold of the motif of my painting, then I can take a break in my research. When I’m painting something passed on a photograph, my goal is not to paint the scene reflected there. Rather, I want to create something based on what I’ve figured out about why this person has been photographed here, or why they are wearing the clothes they have on, and so forth.

If a question comes up as I’m working, then I’ll stop working for a moment to look things up. I do that over and over.

I plan to exhibit my Hailar series in January or February 2023 as my terminal project for the completion of my master’s program. My portraits series focusing on individuals is likely to be the main focus, so it’s crucial that I get a careful grasp on the history of the various ethnic groups. How many painting do I do of which persons? What do I do about the proportions of people from each ethnic group? Even in the catch-all category of Mongolian there were people from various “Mongol” lineages.

Mongolians, Japanese, Chinese, Soviet Russians, Koreans. "Manchurian"s so-called “Five Races Under One Union” is reflected in the Hailar photo album.

At first, I didn’t think I would figure out who these persons were to this extent. When you look at human relationships, you really don’t know where or how this and that person became connected. It is said that everyone in the world is connected to one another through seven degrees of separation. Well, even among the five or six people who are the central figures in this photo album, the interpersonal relationships seem to expand exponentially and unexpected connections spread all over the place.

I had wondered what happened to the Russian who appeared in the Hailar photo album. I did a little checking and found records that when the Red Army came in after "Manchūkuo" collapsed, fearing what would happen he fled first to Shanghai, then to Beijing, and finally to Australia and to Central Asia.

The year 1936 in which the photos in this album were taken was one of chaos. The album offers a record of these persons who crossed paths during that truly eventful year. A decade later, enormous upheavals were taking place once again, and very few of the persons we see in the album were still in that location. I wouldn’t know even if I simply drew the line at 1936. I work to depict the human warmth and the feeling of everyday life that I can pick up on by getting a multifaceted take on what was before and what was after through a variety of materials ranging from public records to private writings. Being able to do that might be what my art is.

*Interviews conducted on April 22, 2022, and June 20, 2022.

JACAR-Produced Glossary

During interviews to Mr.Tsue by JACAR, he used numerous place names, personal names, and the names of specific events and other historical terms came up in the conversation with Mr. Tsue.

Since many of the terms seem unfamiliar to many readers, JACAR prepared a glossary to aid in understanding.

We encourage you to consult it as necessary.

*The terms are listed in the order of their appearance.

- *Hailar (Hairaru)

- Currently, a city located in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China.

Became part of Xing’an North Province after the founding of "Manchūkuo".

To provide for an attack by the Soviet Union, the Kwantung Army constructed a fortress in Hailar in 1937.

The Chinese characters used for “Hailar” are “海拉爾.”

- *Buryats

- A northern subgroup of Mongols who live around Lake Baikal, Hailar, and northern Mongolia.

Originally composed of people from multiple clans, but after Russians invaded into Buryats in the 17th century they came to be known under the collective name of “Buryats.”

- *White émigré

- Refers to members of the so-called “White movement” who opposed the Soviet government established in the wake of the Russian Revolution of October 1917.

- *Northern Xing’an Security Forces

- A unit of the former Manchurian army created in Xing’an North Province after the founding of “Manchūkuo”.

Commanded by Urzhin Garmaev.

- *Shangwei

- An officer’s rank in the “Manchūkuo” army.

Equivalent of “captain.”

- *TERADA Toshimitsu

- Born 1882 in Tokyo.

His educational history included study at the Army Cadet School, the Army Officer Academy, the Army Artillery School, and the Army Field Artillery School. After completing these studies, he joined the former Japanese army and was appointed a second lietuenant in the army artillery.

1924: Studied Mongolian at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages.

1927: Traveled to Mongolia at his own expense, where he met Urzhin Garmaev.

August 1932: Assigned to counterintelligence services in Hailar.

August 1933: Took up position as advisor to the Northern Xing’an Security Forces.

1937: Died of illness in Hailar.

- *Halha-miao Incident (C), Haruha-byō Incident (J), Battle of Khalkhyn Temple

- A conflict that occurred in January 1935 near Khalkhyn Temple (Haruha-byō), located along the border between “Manchūkuo” and the Mongolian People’s Republic.

A unit of the Mongolian People’s Army crossed the Khalkhyn River in action that the Kwantung Army regarded as illegal. The “Manchūkuo” Northern Xing’an Security Forces were dispatched in response, and a large number of military servicemen on both sides were killed and wounded as a result of the clash between the two forces.

- *OKAMOTO Toshio

- Studied Mongolian at the Osaka School of Foreign Languages (predecessor to the present-day Osaka University of Foreign Studies).

Served as an interpreter to the Northern Xing’an Security Forces’ commander Garmaev. Passed away in 2004.

- *Urzhin Garmaev

- A “White” Russian who resettled from Zabaikal to Hulunbuir.

From 1932 to 1944, served as commander of Manchūkuo’s Northern Xing’an Security Forces.

He was interrogated by the Kwantung Army in 1936 and Xing’an North Province governor Ling Sheng was arrested and executed over suspicions that he colluded with the the Mongolian People’s Republic. However, he was released due to the assistance made by TERADA Toshimitsu.

After the war’s conclusion, he surrendered himself to the Red Army’s local headquarters. Executed in Moscow in 1947.

- *Manzhouli Conference

- A series of conferences held in the wake of the creation of “Manchūkuo” to resolve the frequent border conflicts that arose between “Manchūkuo” and the Mongolian People’s Republic.

Among the conferences’ participants was Northern Xing’an Security Forces commander Urzhin Garmaev.

The conferences were held from 1935 to 1937, but produced no results.

- *Merse (Chinese name: Guo Daofu)

- Born 1894 in Hulunbuir.

Politician deeply involved with the Inner Mongolia revolutionary movement of the 1920s.

In 1928, led an armed uprising seeking to restore autonomy of Inner Mongolia, but was rebuffed.

Date of passing unknown.

- *Fu Zuoyi

- Kuomintang military officer and politcian.

After graduating from the Baoding Military Academy in 1918, joined Yan Xishan’s Shanxi army.

In August 1928, assumed the positions of supreme commander, 5th Corps, 3rd Army Group, National Revolutionary Army; and Commander, Tianjin Garrison.

Assumed office of governor of Suiyuan Province in December 1931.

Passed away in 1974.

*The following literature was consulted by JACAR in preparing the glossary.

- Borjigin Burensain, ed., Uchi-Mongoru o shiru tame no 60-shō (Akashi Shoten, 2015).

- Komamura Kichie, “Rekishi no yami ni hōmurareta: Manchūkuo no Mongorujin shōgun” (Shinchō 45, December 2001).

- Makinami Yasuko, Go-sen-nichi no guntai: Manshū kokugun no gunkan-tachi (Sōrinsha, 2004).

- Mandakh Ariunsaikhan, “Manshūri kaigi ni kansuru ichikōsatsu” (Hitotsubashi ronsō, vol. 134, no. 2, 2005).

- Manshū Kōhō Kyōkai, Manshūkoku no genjūminzoku, Manshū Kōhō Kyōkai, 1936).

- Military Archives, National Institute for Defense Studies, Senshi sōsho: Kantō-gun (1)—Tai-So senbi, Nomonhan jiken (Asagumo Shinbunsha, 1969).

- Mori Hisao, Nihon rikugun to Uchi-Mō kōsaku: Kantōgun wa naze dokusō shita ka (Kōdansha, 2009).

- Oikawa Takuei, Teikoku-Nihon no tairiku seisaku to Manshū kokugun (Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 2019).

- Ozawa Chikamitsu, Hishi Manshū kokugun: Nikkei gunkan no yakuwari (Kashiwa Shobō, 1976).

- Borjigin Sergelen, Manchūkuo no tōbunai Mongoru tōchi (Hongō Hōsei Kiyō, no. 11, 2002).

- Takinami Hideko, “‘Hairaru no chichi’ Terada Toshimitsu-taisa no shūhen: Maboroshi to kieta ‘yūtopia’” (Nakamura Yoshikazu, Naganawa Mitsuo, and Podalko Petr, eds., Ikyō ni ikiru, IV: Rai-Nichi Roshiajin no ashiato, Seibunsha, 2008).

- Tanaka Katsuhiko, Nomonhan sensō: Mongoru to Manshūkoku (Iwanami Shinsho, 2009).

- Yamada Tatsuo, ed., Kindai Chūgoku jinmei jiten (Zaidan-hōjin Kazankai, 1995).

- Yang Haiying, Nihon rikugun to Mongoru (Chūkō Shinsho, 2015).

- Emgenuud Imin, “Kindai ni okeru Furenboiru chiiki no keisei: ‘Baruga’ kara ‘Furenboiru’ ni naru made” (Shōwa Joshi Daigaku Daigakuin Seikatsu Kikō Kenkyūka Kiyō, no. 30, 2021).

- ZUrgedei Taibung, “Guo Daofu (Merse) to sono jidai: 1928-nen Furunboiru Seinentō hōki o chūshin ni,” trans. Tanaka Tsuyoshi (in Tanaka Hitoshi, et al., eds., Kyōshinka suru gendai Chūgoku kenkyū, Ōsaka Daigaku Shuppankai, 2012).

- Planning and composition:

- Ōkawa Shiori, Assistant Researcher, Japan Center for Asian Historical Records

- General editing and glossary creation:

- Kaneko Takasumi, Researcher, Japan Center for Asian Historical Records