JACAR Newsletter

JACAR Newsletter Number 45

December 26, 2024

Special Feature

An Introduction to ‘Postwar Diplomatic Records” from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Part 1)

JACAR Director-General HATANO Sumio

Introduction

Starting in 2016, in response to strong demand from users and the academic community, and with the cooperation of both the Diplomatic Archives at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) and the National Archives of Japan, the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) has been receiving deliveries of digitized images of diplomatic records and administrative documents from the postwar period and making those images broadly available to audiences both foreign and domestic.

We also receive frequent inquiries regarding exactly what sorts of records those items are. Accordingly, I would like to provide you with an overview—divided up into several parts—about the “postwar diplomatic records” that have been provided by the Diplomatic Archives.

The “postwar diplomatic records” delivered to JACAR comprise those diplomatic records already released to the public whose temporal scope basically runs from the end of World War II to the Sino-Japanese normalization of relations and Okinawa’s reversion in 1972, and that are included the category of “Asian historical records[1]” in accordance with JACAR’s founding intent.

The already-released diplomatic records that meet this standard in principle can also be viewed through the Diplomatic Archives. However, when providing them to JACAR, they go through another screening process at MOFA and only then are successively posted to the JACAR database. Accordingly, this does not necessarily mean that the diplomatic records viewable at the Diplomatic Archives automatically can be viewed through JACAR.

At JACAR, in adding the provided diplomatic records to our database, mindful of convenience to users, we offer up these records broadly with more detailed search functions included based on JACAR’s unique search system (which includes such features as previews that render the first 300 characters of the document as text).

To begin this overview, I will start by explaining simply how diplomatic records are released at MOFA.

[1] The Mechanism for the Release of Postwar Diplomatic Records

Currently, MOFA uses one of three methods broadly speaking for releasing postwar diplomatic records.

The first method is that of “voluntary release,” which MOFA has pursued since 1976 based on the international “thirty-year rule” standard. At the time, this was a voluntary measure that MOFA took ahead of other ministries and agencies as part of its administrative services. That said, even before WWII MOFA had been proactively working to release diplomatic records, so in a sense this was also a continuation of that tradition.

Today, this “voluntary release” has been transitioning from the level of “administrative service” to that of a release performed based on the Public Records Management Act (Public Records and Archives Management Act, came into force in 2011). MOFA in 2010 had just established a rule that records that had gone 30 years since they were obtained or created would “in principle be released.” It also set down the procedures for that operation, and so reforms for which an internal screening had been completed would successively be transferred to the Diplomatic Archives and made public.

The second method is based on the Information Access Law (Law Concerning Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs, came into force in 2001). This method calls for disclosing even those records for which 30 years have yet to pass since they were obtained or created in response to an information access request from an individual or group and presenting them for viewing and use. Accordingly, not all of the diplomatic records released under the “thirty-year rule” are newly released; there are more than few cases of records that have already been made public.

The third method has been to compile and publish already-released records in Nihon gaikō bunsho [Documents on Japanese Foreign Policy]. This project has been ongoing since 1936. In 2006, in parallel with the publication of documents from the prewar period through to 1945, MOFA began publication of the three-volume “San Francisco Peace Treaty” segment. This marked the first step in the full-fledged compilation and publication of postwar materials. An important motivation for compiling the postwar documents was the release over 2001 and 2002 of “Heiwa jōyaku no teiketsu ni kansuru chōsho” [Records concerning the conclusion of the Peace Treaty] arising from a usage request based on the Information Access Law. As is well-known, this document is a compilation of the relevant records that the late Nishimura Kumao—chief of the Treaty Bureau during the years around the time when the San Francisco Peace Treaty was concluded—prepared himself after his retirement.

In the aftermath, compilation and publication of Nihon gaikō bunsho for the postwar period has gone smoothly forward with 21 volumes covering those years having been published to date (including the pre-1945 years, the series now spans 229 volumes)[2].

Of those postwar diplomatic records released through the three above methods, the records that have been digitalized and provided to JACAR are those that have been released through the first one.

[2] An Overview of the Postwar Diplomatic Records

The Catalog of “Postwar Diplomatic Records” provided to JACAR by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs broadly divides up all of the provided records in question into major categories. It lists the “Call Number” for each file at the Diplomatic Archives, the “Title” (“File Title,” in JACAR parlance), the JACAR reference code, and the start and end dates for the documents included in the file.

Beginning with this article and over several further installments, following the catalog’s categorization scheme I will introduce you to some of the material contained in these records.

I. Records on the Acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration

The content of voluminous file titled, “A matter related to the Potsdam Declaration acceptance” [Pottsudamu sengen judaku kankei ikken] can be broadly divided up into two groups.

The Potsdam Declaration and MOFA

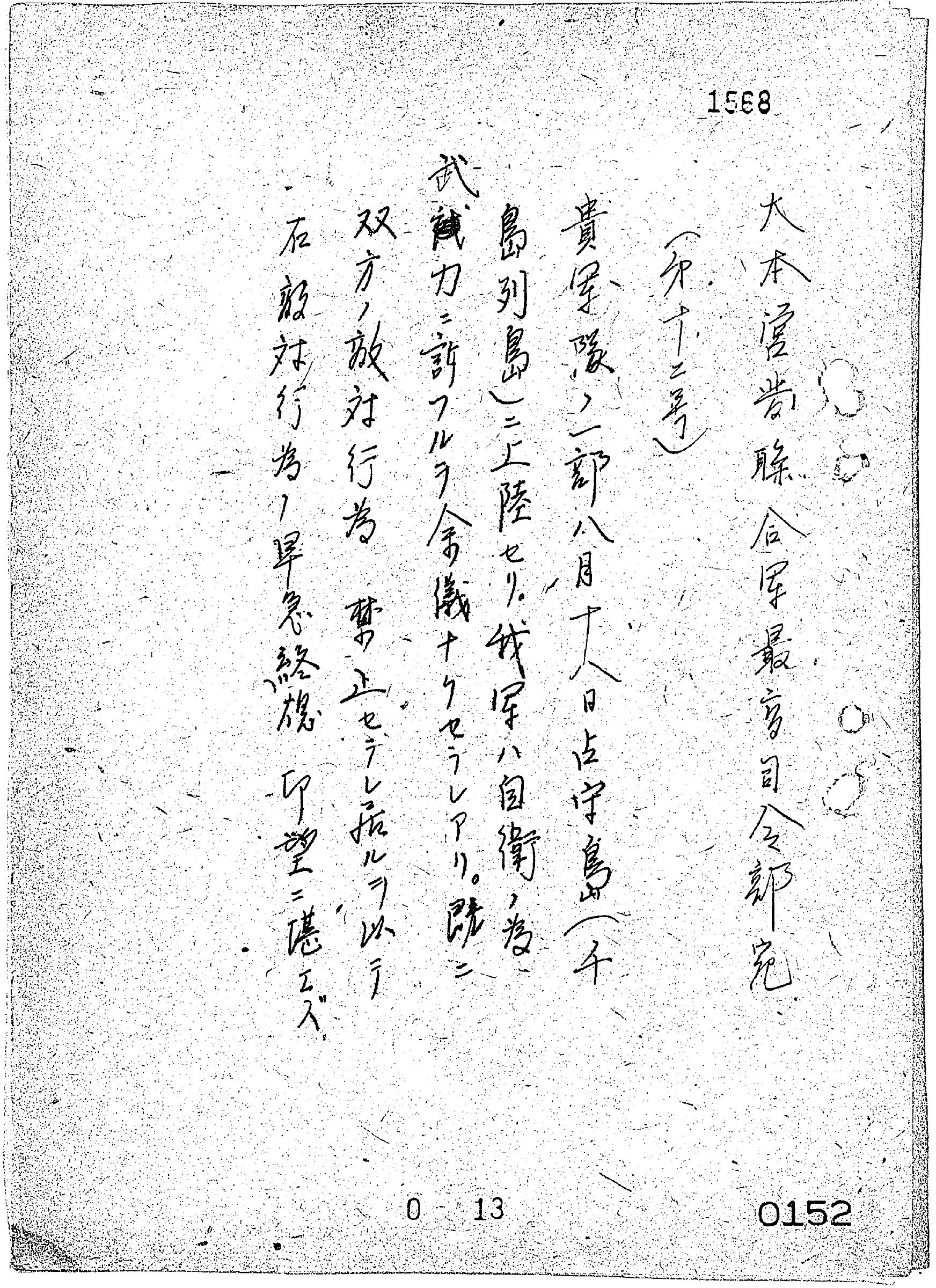

This is a document that sets forth the thinking and actions of MOFA’s senior officials regarding interpretations and responses to the Potsdam Declaration of July 26, 1945, which served to urge Japan’s surrender (see Image 1).

[Image 1] Item name: “(Appendix 1) U.S., U.K. and China, study of the Potsdam Declaration” [Fu 1: Bei-Ei-Shi Pottsudamu sengen no kentō] (Ref. B18090000800, image 2).

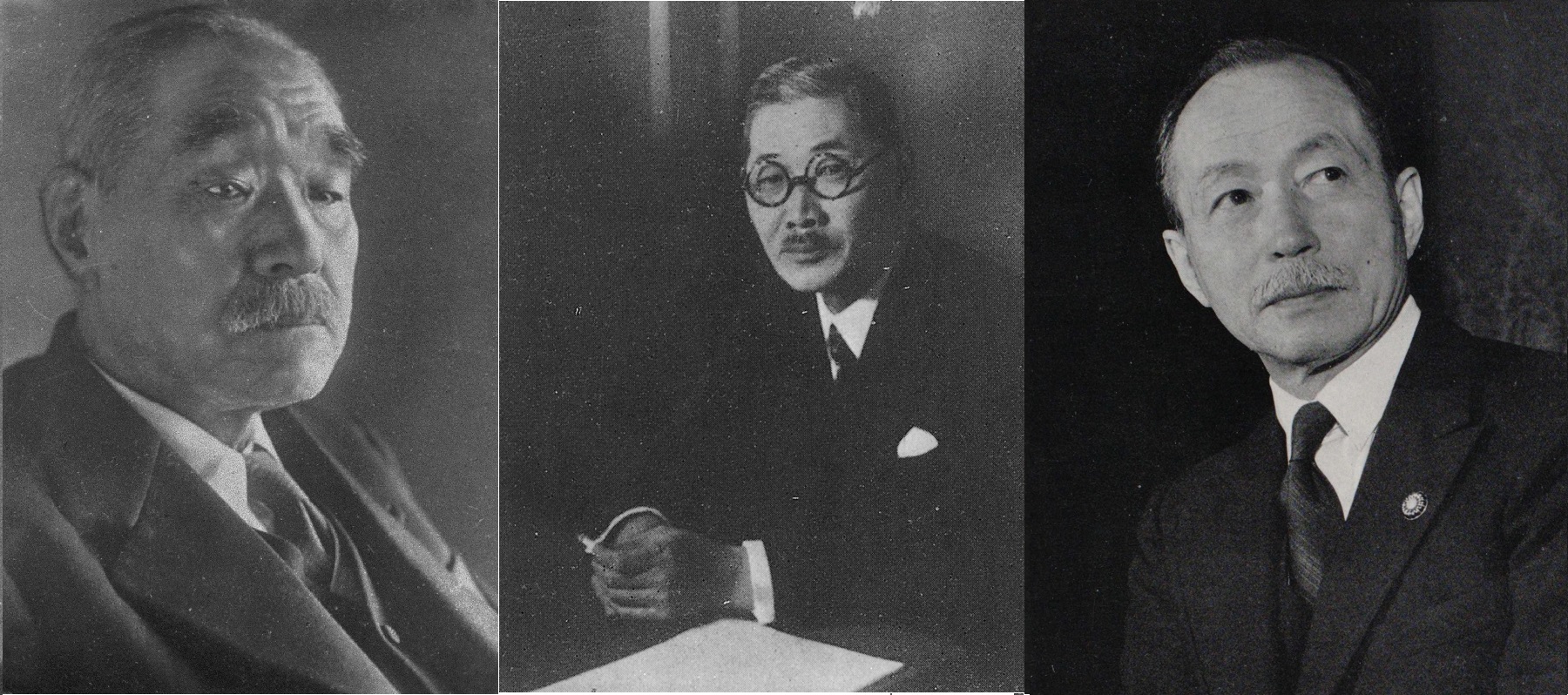

MOFA senior officials and Foreign Minister Tōgō Shigenori needed no time to reach an accord on the principled acceptance of the Declaration. The grounds for this included such aspects as “unconditional surrender” being restricted to Japan’s armed forces (Article 13) and therefore it could be understood as a proposal for “peace with conditions,” and, with regard to the emperor system, it was thought that once “there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government,” the occupying forces would be withdrawn (Article 12).

However, officials such as Foreign Minister Tōgō decided with regard to the issue at hand that it would be prudent to persist with a “no comment” to mean the government would not declare its intent, and this became the stance of MOFA and of Prime Minister Suzuki Kantarō. This is because the government at that moment was making tentative overtures about dispatching an envoy to the Soviet Union, anticipating that it could help to mediate a peace. But Prime Minister Suzuki was not able to sustain the “no comment” policy, and at a press conference held in the afternoon of July 28, he ended up issuing the statement, “the Japanese government does not see it [the Potsdam Declaration] as a matter of much significance. We have no comment to make on it [mokusatsu suru].” The “mokusatsu” statement was seen by the Allied powers as a de facto “rejection,” and as signaling a determination to the continue the war. It is regarded as having become one of the pretexts for the dropping of the atomic bombs.

Around this time, Ambassador Satō Naotake in Moscow had been sending one telegram after another to Tōgō in which he said that it was inconceivable that the U.S. and U.K. would ease off regarding unconditional surrender and that there was no point to dispatching a special envoy. Meanwhile, the fact that the Soviet Union had not signed on to the Potsdam Declaration led to exaggerated expectations about winning the Soviets’ favor and the possibility of dispatching a special envoy.

[Image 2]: Prime Minister Suzuki Kantarō (left), Foreign Minister Tōgō Shigenori (center), and Ambassador to the Soviet Union Satō Naotake (right)

Source: National Diet Library, “Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures” <https://www.ndl.go.jp/portrait/e/>, also partially compiled at JACAR.

In order to understand the political process that led to the acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration, including the course of events that led to the “mokusatsu” statement, it will be necessary to take up other records and literature. In particular, MOFA records by themselves are insufficient for gaining a deeper understanding of what the leaders of the government and the armed forces thought and the actions they took during the critical period from August onward—spanning the dropping of the atomic bombs and the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan—that led to the second imperial decision of August 14.

Additionally, in “A matter related to the Potsdam Declaration acceptance Vol.3 (End of the war-related record of investigation)” [Pottsudamu sengen judaku kankei ikken, Dai-3-kan (Shūsen kaneki chōsho)] (Ref. B18090003900)—one volume of the documents collected within the file under that general title—we find such deeply interesting items such as “26. Urgent establishment of voluntary and summary measures (draft proposal) (October 9, 1945)” [Jishuteki sokketsuteki shisaku no kinkyū juritsu ni kansuru ken (shian) (20.10.9)] [Ref. B18090006700]). This document forecasts the direction of US reforms to Japan’s governance system as it explains the necessity for Japan to carry out reforms through “voluntary” intent. I will take that particular item up in detail in another installment in connection with constitutional revision.

War Termination Around Asia

These are telegrams and documents that convey the chaotic situation on the ground around the time of the cessation of hostilities, based on information produced by diplomatic missions around the Asia-Pacific region.

General Order No. 1 (known in Japanese as “Ippan meirei dai-ichi-gō”) (see below), issued by the Office of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), ordered that all Japanese armed forces whether in Japan or abroad cease hostilities and lay down their arms, regardless of any local special circumstances.

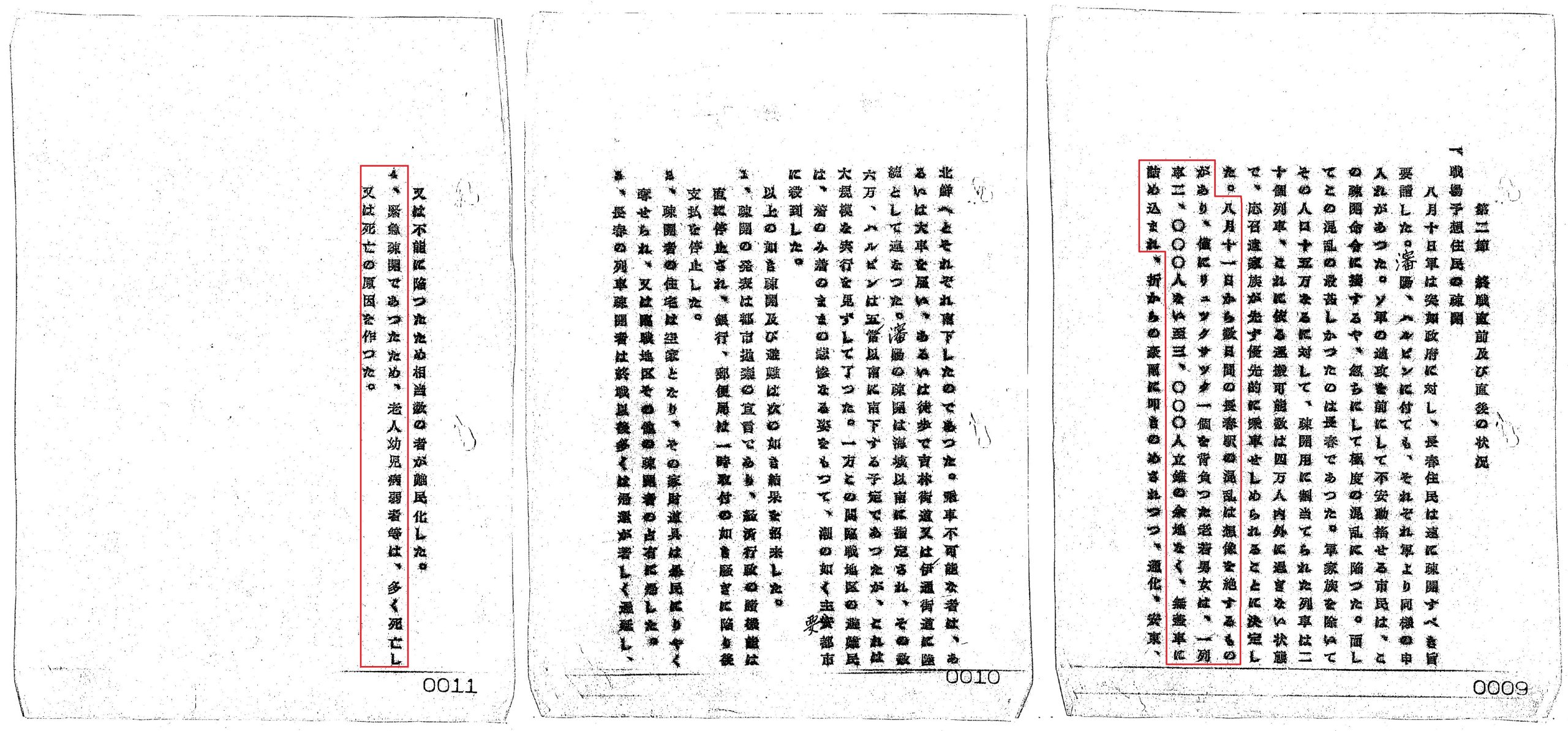

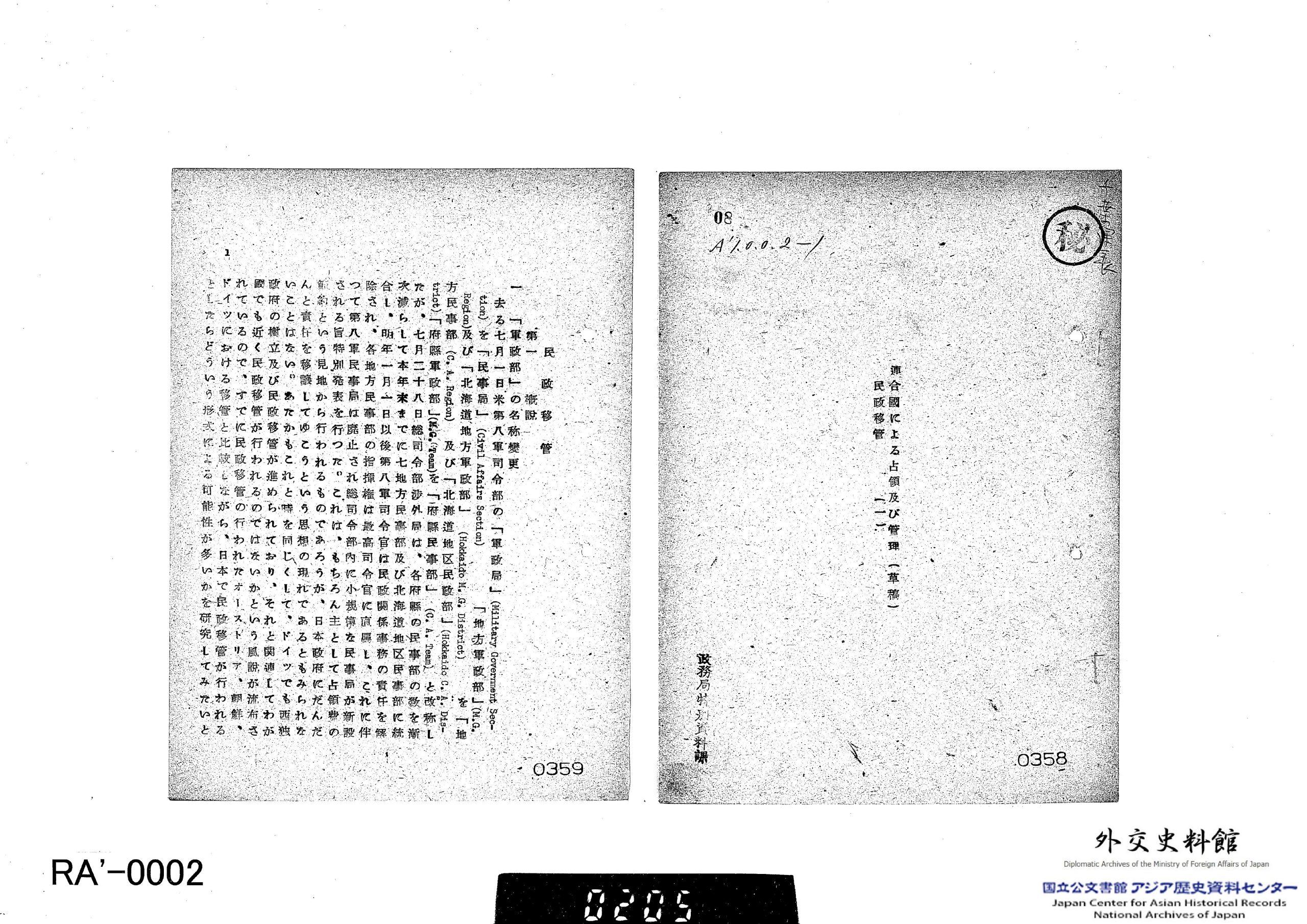

[Image 3] Item: “(2) The telegraph emitted by the Japanese government Imperial Headquarters to the Allied Powers Supreme Headquarters from August, 1945” [Nihon seifu Daihon’ei-hatsu, Rengōkoku saikō shireibu ate denshin, ji-Shōwa nijū-nen hachi gatsu] (Ref. B18090011000, image 19).

However, fierce combat continued intermittently in the Chishima (Kuril) Islands, Karafuto (Sakhalin), and Manchuria. For example, Soviet troops landed on Shumshu Island in the Chishima (Kuril) chain on August 18. The Japanese side sent a telegram to SCAP that pleaded, “Our forces have had no choice but to resort to arms for self-defense. Since both sides have already halted hostilities, we cannot bear our longing for the immediate end to hostile activities” (see Image 3: “From Imperial General Headquarters to SCAP (No. 12). In Item: :” (2) The telegraph emitted by the Japanese government Imperial Headquarters to the Allied Powers Supreme Headquarters from August, 1945” [Daihon’ei-hatsu, Sōgō Rengōkoku saikō shireibu ate (dai-12-gō): Kenmei “Nihon seifu Daihon’ei-hatsu, Rengōkoku saikō shireibu ate denshin, ji-Shōwa nijū-nen hachi gatsu”] [Ref. B18090011000, image 19]).

In mainland China, the situation was such that Nationalist and Communist Chinese forces fought to advance into areas that had been occupied by the Japanese armed forces, and demands were made for uncontrolled disarmament of the latter. “Local ceasefire negotiations” and “voluntary decisions” on disarmament were deemed necessary. This earnest desire was conveyed to the Allied powers before the signing of the surrender in the form of “Items to be agreed upon in advance” (Jizen ryōkai toritsuke jikō) (see “Rengōkoku saikō shireibu ni taisuru jizen ryōkai toritsuke jikō; in Item: “(3) End-of-War Settlement general matters (including English translations of August 14 Imperial edict and August 17 Imperial edict given to the Army and the Navy) reference should be made to (9) of this volume. from August, 1945” [(3) Shūsen shori ippan jikō” [8.14 Shōsho, 8.19 Rikugun ni tamawaritaru Shōsho Eiyaku o fukumu. Honsatsu (9) Sanshō no koto. Ji Shōwa 20-nen 8-gatsu] [Ref. B18090012400, images 22–25] etc.).

The situation at the end of the war around Asia in general is covered in a document dated September 28, 1945 titled, “‘The Situation Regarding Handling the Cessation of Hostilities Throughout East Asia’ According to the Dōmei News Agency” [Dōmei Tsūshin ni yoru ‘Tō-A kakuchi no shūsen shori jōkyō] (ibid., images 60–68). However, the chaos, panic, and calamity in the Japanese communities differed from region to region, and their repatriation was not easy. For example, section two (image 4) of “The Demise of Manchūkuo and the Situation of Resident Japanese” [Manshūkoku no shūen to zai-Man houjin no jōkyō] (Item: “1. Manchuria from August 1945 [1. Manshū, ji Shōwa 20-nen 8-gatsu] [Ref. B18090018500, images 5–6]) conveyed that 150,000 Japanese in Changchun who were ordered to immediately evacuate right after the Soviet invasion poured into Changchun station. It described the situation, saying “The confusion at Changchun station for several days after August 11 was one of confusion beyond imagination. Two to three thousand men and women young and old, each carrying little more than a single rucksack, were crammed to capacity on the open freight cars of a single train,” and said in summary, “Because it had been an emergency evacuation, it led to the deaths of or created the causes of death for many elderly, infant, and sickly people.”

[Image 4] Item: “1. Manchuria from August 1945 [1. Manshū, ji Shōwa 20-nen 8-gatsu] (Ref. B18090018500, images 5–6), enclosure in red added by JACAR.

II. The Occupation of the Japanese Mainland and Military Administration by the Allied Forces

Acceptance of the Instrument of Surrender

On August 16, immediately after the acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration, General Douglas MacArthur—who had been appointed as SCAP—sent a request through the Swiss government for “emissaries” representing the Japanese government to be sent to Manila. The Japanese government was not certain if the duty of these emissaries was to sign the surrender documents or if it was to hold preliminary discussions. However, it soon became clear that their main duty was to discuss the guidelines for the occupation, and the government dispatched a delegation led by Deputy Chief of Staff Lt. General Kawabe Torashirō (Army).

On August 20, the Kawabe delegation returned to Japan having been handed detailed guidelines for the occupation, along with three documents: (1) an Imperial proclamation, (2) the Instrument of Surrender, and (3) General Order No. 1. Document 1 was to be promulgated as an imperial rescript at the same time the instrument of surrender was signed. It stated that the emperor accepted the terms of the Potsdam Declaration, and ordered representatives of the Imperial General Headquarters and the Japanese government to sign the surrender instrument in the emperor’s name.

Document 2, the Instrument of Surrender, set down “the unconditional surrender . . . of all Japanese armed forces and all armed forces under Japanese control,” and stipulated that the authority of the emperor and the Japanese government to rule would be “subject to the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers” in order to effectuate the terms of surrender. Document 3 ordered all Japanese forces to cease hostilities, lay down their arms, and to whom those forces located overseas should surrender to.

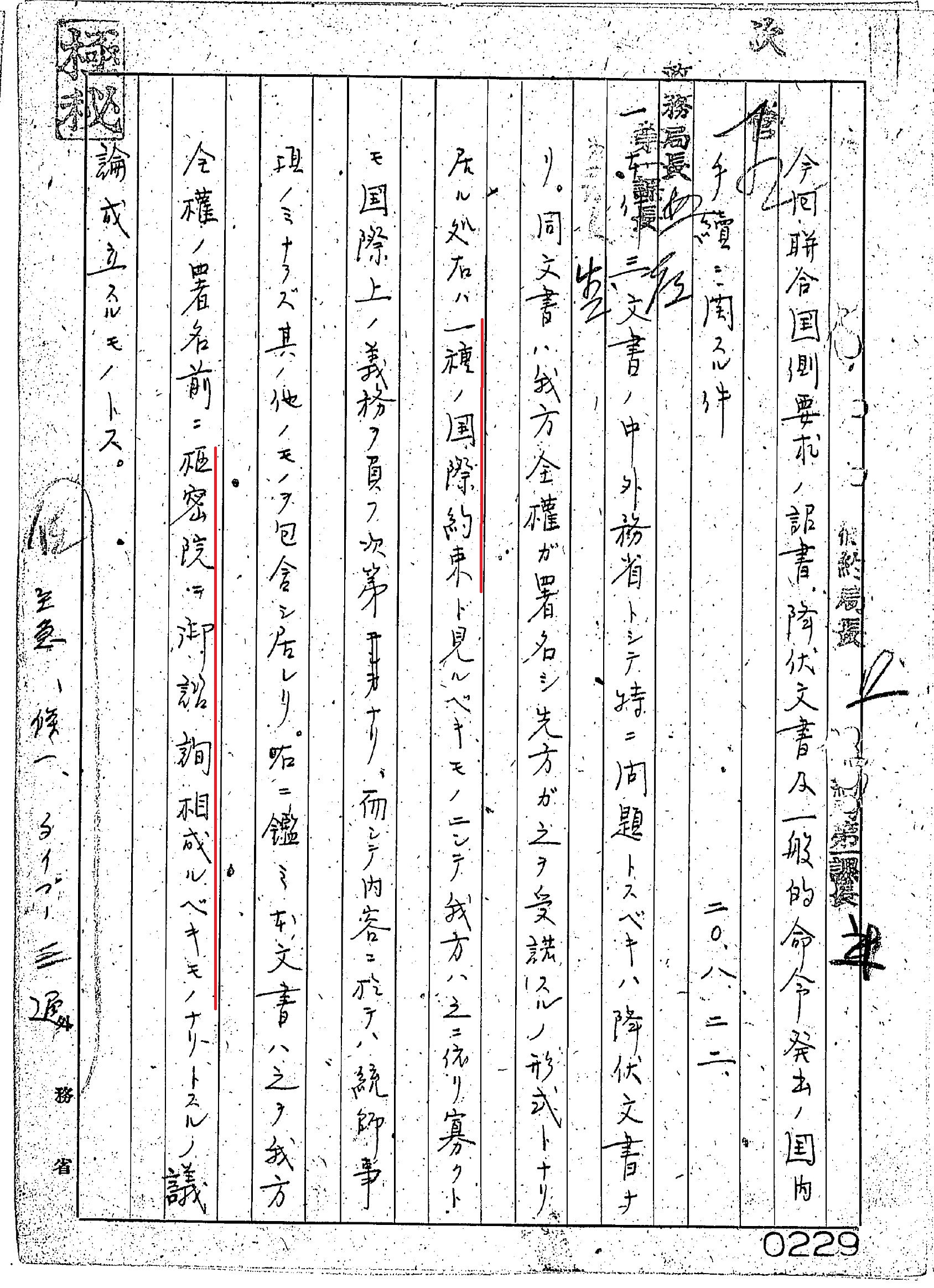

[Image 5] Item: “(2) Imperial edict, instrument of surrender and the General Order No.1 from August, 1945” [Shōsho, Kōfukubunsho oyobi Ippan Meirei Dai-1-gō, ji Shōwa 20-nen 8-gatsu] (Ref. B18090009300, image 27). Red lines added by JACAR.

MOFA regarded the Instrument of Surrender as a sort of “international promise” that took the form of “our plenipotentiaries sign it and the other side accepts it.” They assumed that if it was an international treaty, the procedure called for a consultation at the Privy Council prior to the plenipotentiaries signing (see Image 5). In the end, as with the acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration, the consultation was left out and consent given after the fact.

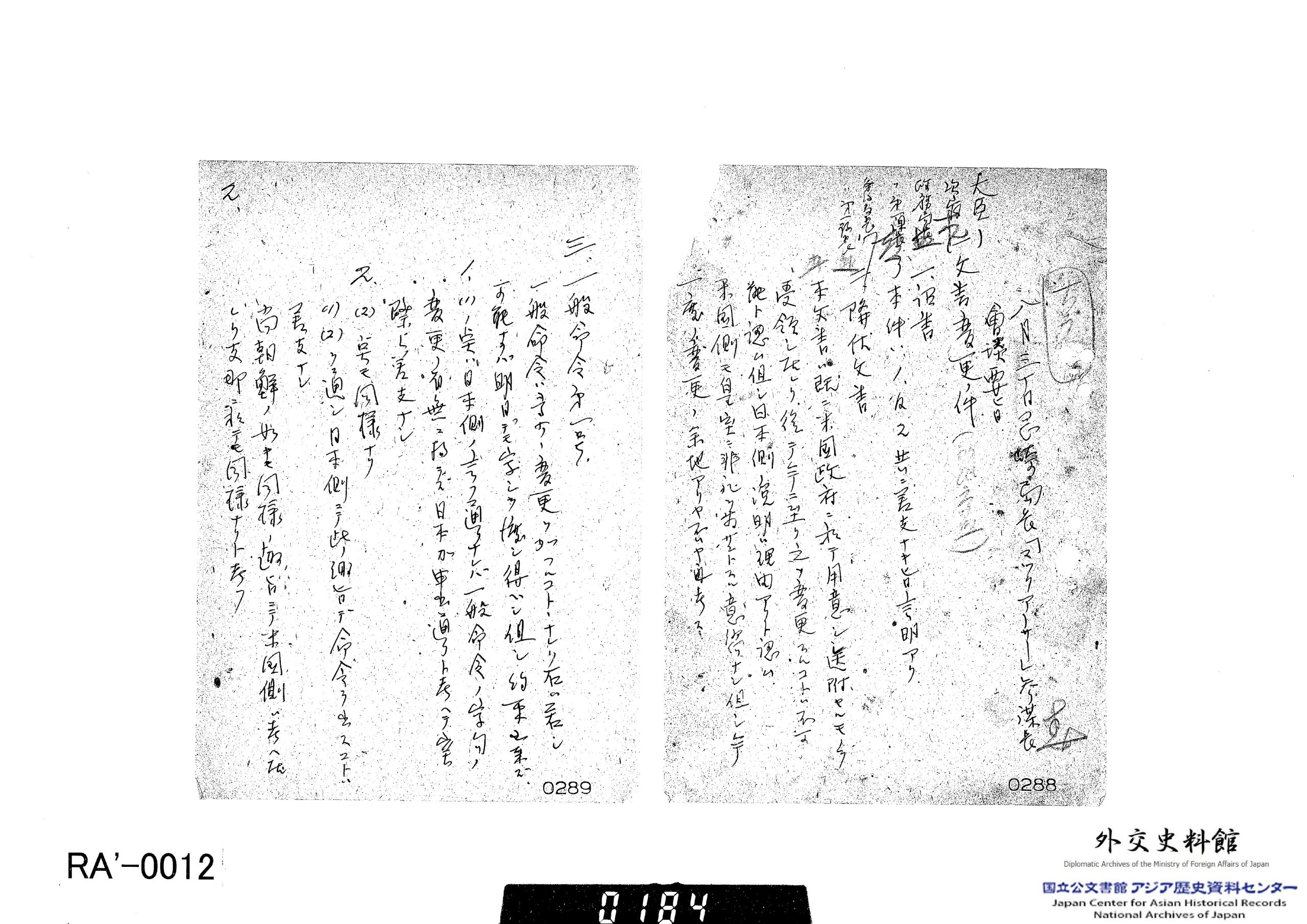

Requests for revisions to the three documents were submitted together at an August 30 meeting between MacArthur and Okazaki Katsuo (see Image 6; Item: “1. The meetings between Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (including the dignitaries of Allied Powers) and the prime minister (including the dignitaries of government) / 21) Summary of the meeting of Bureau Director Okazaki and Chief of Staff for MacArthur (August 30, 1945)” [1. Rengōkoku Saikō shireikan (Rengōkoku yōjin o fukumu) Naikaku sōridaijin (Seifu yōjin fukumu) kan kaidan kankei / 21) Okazaki-kyokuchō “Makkāsā”-sanbōchō kaidan yōshi (Shōwa 20.8.30)] [Ref. B17070026200]). For example, in accordance with the wishes of the army, they asked that the text in General Order No. 1 reading “to disarm completely all forces” be changed to read “to disarm completely, in such a manner as is suited to the peculiar conditions in each locality.” Although these were not officially accepted, at the stage of carrying out the disarmament consideration for “peculiar conditions” was de facto accepted.

[Image 6] Item: “1. The meetings between Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (including the dignitaries of Allied Powers) and the prime minister (including the dignitaries of government) / 21) Summary of the meeting of Bureau Director Okazaki and Chief of Staff for MacArthur (August 30, 1945)” [1. Rengōkoku Saikō shireikan (Rengōkoku yōjin o fukumu) Naikaku sōridaijin (Seifu yōjin o fukumu) kan kaidan kankei / 21) Okazaki-kyokuchō “Makkāsā”-sanbōchō kaidan yōshi (Shōwa 20.8.30)] (Ref. B17070026200, image 2).

The Enactment of Military Government

General MacArthur flew from Manila to arrive at Atsugi Airfield as SCAP on August 30, two days after the arrival of an advance party. MacArthur went on at once to Yokohama, and then on to Tokyo on September 17. On October 2, he established the General Headquarters for SCAP (GHQ/SCAP) at the Dai-ichi Life Insurance Building in Hibiya. It was from this moment that the occupation of Japan began in earnest. (The GHQ was abolished with when the Treaty of Peace with Japan came into force on April 28, 1952, also bringing the occupation of Japan to an end.)

[Image 7] MacArthur just after his arrival at Atsugi Airfield (“USA C-1732 General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, U.S. Army [second from right].” Photograph from the Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives), partially edited by JACAR.

Throughout the occupation period, the Allied armies—mainly US forces—were stationed in all parts of the Japanese mainland. The “Occupation Force” as it was called totaled 300,000 personnel by the end of October when their deployment to those various locations was nearly completed, and reached a peak size of 450,000 personnel by the end of December.

“Items Related to the Allied Forces’ Occupation of the Japanese Mainland and Military Government” [Rengōgun no hondo shinchū narabi ni gunsei kankei ikken]—a massive file comprising more than 200 volumes—conveys that the occupation covered everywhere from Hokkaido to Kyushu, but the extent of it varies from region to region. For example, there are few records that remain regarding the situation during the early stages of the occupation in Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe.

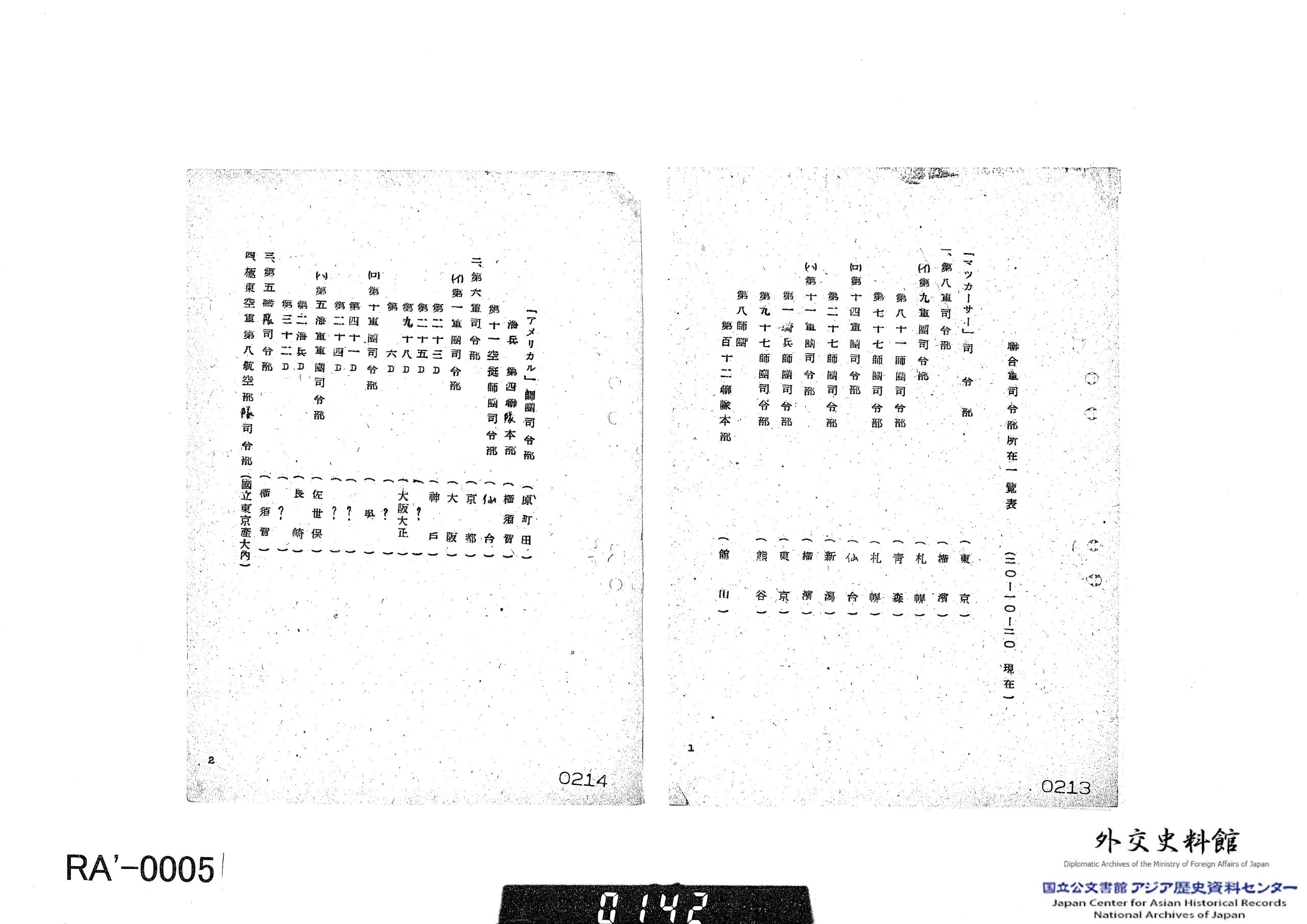

[Image 8] “List of Allied Forces Headquarters Locations (as of October 20, 1945).” Item: “5. Military Administration organization and personnel (organization) /3) matters related to army corps military administration department / Partition 1 ” [5. Gunsei soshiki oyobi jinji (soshiki) / 3) Kaku gundan gunseibu kankei / bunkatsu 1] (Ref. B17070006400, image 2)

Initially, the nucleus of the forces occupying Japan rested with the Eighth Army (Yokohama) and Sixth Army (Kyoto), both of which were under the umbrella of the Far East Command (whose predecessor was the U.S. Army Forces in the Pacific) (see Image 8). Wakayama was the first territory to be occupied by the I Corps, Sixth Army, which had jurisdiction over central Honshu stretching from Kobe, Osaka, and Kyoto to Toyama, Shizuoka, and Nagano. The I Corps’ occupation began in late September, with a first wave comprising 92,000 troops and a second wave of 23,000 landing. According to diplomatic records, in Wakayama the question of how to deal with supplying the large amount of labor demanded by the Occupation Forces was a major issue, and 90,000 laborers were mobilized (among others, see “October 13, 1945: A Report on the General Situation Regarding War Termination Liaison Matters in Wakayama,” in Item: “4. The matters related to stationing of U.S. Army in various districts (excluding Atsugi and Yokohama) -including situation and movement report of Allied Forces- from September, 1945 / (5) The matters related to stationing of troops in Kinki District” [4. Kakuchiku (Atsugi, Yokohama o nozoku) ni okeru Beigun no shinchū kankei: Rengōgun no jōkyō, dosei hōkoku o fukumu, Shōwa 20-nen 9-gatsu/(5) Kinki chikku shinchū kankei] [Ref. B18090046500, images 23–24]). One can infer that conditions were similar in other occupied areas.

Subsequently, the Sixth Army headquarters was dissolved at the end of December 1945, with the Eighth Army taking over command of its units and administration of the occupation in January 1946. With this, all 46 prefectures came under the control of the Eighth Army.

In February 1946, the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF)—comprised mainly of Australian forces—was added to the Occupation Forces. Headquartered in Kure, Hiroshima Prefecture, the BCOF initially had jurisdiction over the five prefectures of the Chūgoku district and the four on Shikoku, with 36,000 troops at its peak. However, owing to troop reductions, by December 1948 its jurisdiction covered only Hiroshima Prefecture and Iwakuni in Yamaguchi Prefecture.

Under the Eighth Army’s command, local military government organizations were set up in the major regions, and military government teams were set up in each prefecture that had contact with the prefectural governments. The teams’ purpose, however, was not to execute occupation policy in the prefectures, but rather to supervise the execution of occupation policies and pass information back up to their higher-ups.

The basic duty of the Occupation Forces was limited to the function of supervision over “compliance with the directives of the Supreme Commander.” They had taken the form of “indirect rule,” where, rather than issue orders directly to the Japanese people, they instead issued orders to the Japanese government in the forms of memoranda and directives and lay the obligation on that government to carry out those orders.

In the early stages when the policy of “indirect rule” was not yet thoroughly implemented, there were more than a few instances of controversies being created from dealing with matters with a sensibility that came close to direct rule by military government. Presented here a number of deeply interesting examples.

The “Direct Military Government” Crisis: The Issue of the Three Proclamations

On the afternoon of September 2, immediately after the ceremony for the signing of the Instrument of Surrender, Ambassador Suzuki Tadakatsu (Director, Yokohama Liaison Office) was summoned by Deputy Chief of Staff Richard Marshall and told that the Occupation Forces would be stationed in Tokyo. At the same time, he was shown the text of three proclamations that were scheduled to be announced on the morning of the next day. The first one read in part, “All powers of the Imperial Japanese Government, including the executive, legislative, and judicial, will henceforth be exercised under [General MacArthur’s] authority.” It plainly laid out a policy for direct rule by a military government. The second stipulated provided for military trials for persons who violated occupation policy, while the third stipulated that supplemental military currency marked “B” would be regarded legal tender and circulate at the same rate as the Japanese yen (Bank of Japan notes).

A surprised Suzuki immediately reported to his government. Understanding the three proclamations to mean direct military government, the Japanese government held an extraordinary cabinet meeting. It decided to request that the proclamations be suspended, and at midnight dispatched War Termination Central Liaison Office Director Okazaki Katsuo to Yokohama. Okazaki asked Chief of Staff Richard Sutherland that an embargo be placed on the announcement of the proclamations for the time being. Sutherland accepted the request, and directed all units to suspend the plan.

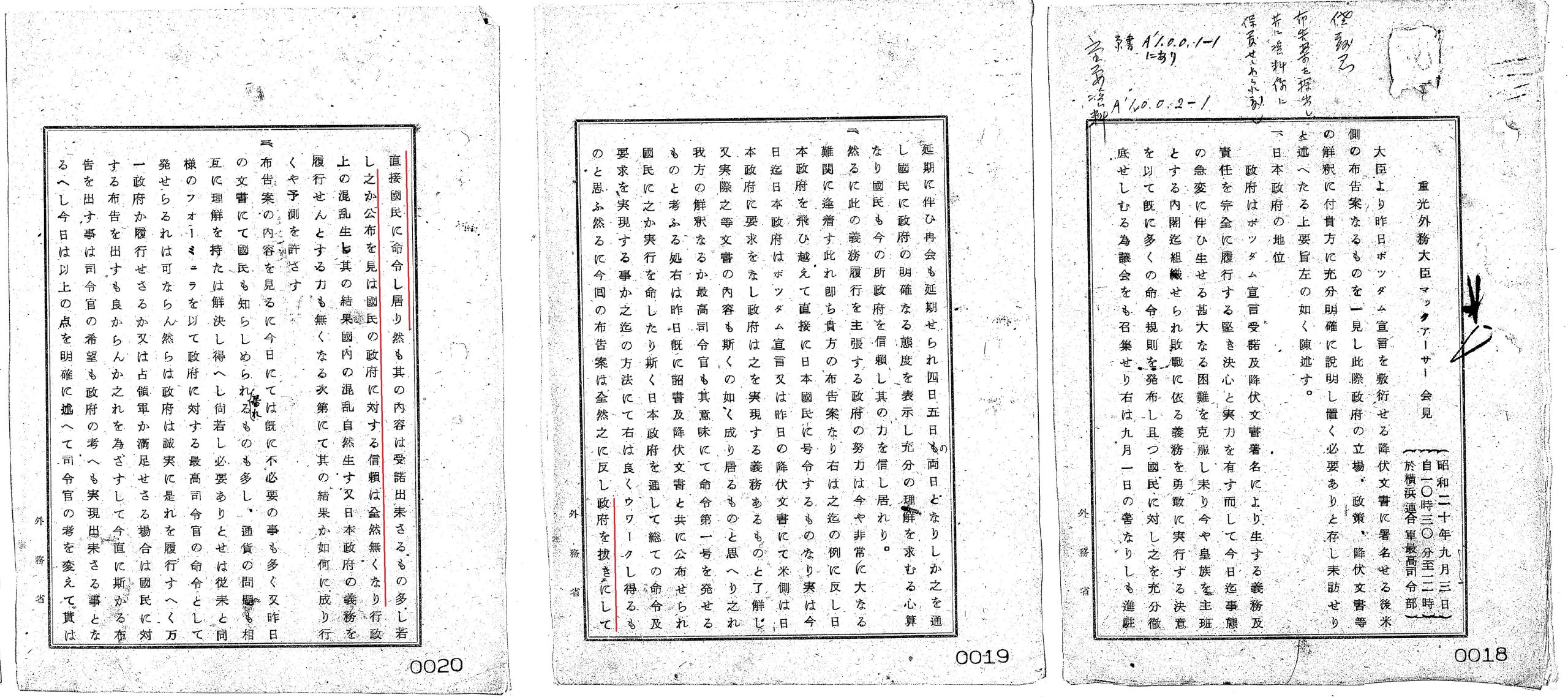

[Image 9] Item: “1. General matters / 2) Proclamation (including the interview of Minister of Foreign Affairs Shigemitsu and MacArthur)” [1. Ippan /2 Fukoku kankei (Shōwa 20-nen 9-gatsu 3-ka, Shigemitsu Gaimudaijin to Makkāsā kaiken kankei ari)] (Ref. B17070000700, images 2–3). Red lines added by JACAR.

Later on the morning of the 3rd, thanks to the intercession of Ambassador Suzuki, Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru met with MacArthur and again requested that the proclamations be suspended. Shigemitsu asserted that the content of these draft proclamations giving orders to the people directly was unacceptable, and that if they were promulgated their trust in the government would be lost and this would invite tremendous political chaos (see Image 9). MacArthur promised to withdraw the proclamations on the grounds that the Allied powers did not intend to destroy Japan, and also promised that if the content of the proclamations were to be executed it would be done through the Japanese government. Furthermore, on the 4th Shigemitsu met with Chief of Staff Sutherland and obtained a promise that use of the “B” currency would be suspended (see, among others, Item: “1. General matters / 2) Proclamation (including the interview of Minister of Foreign Affairs Shigemitsu and MacArthur)” [1. Ippan /2 Fukoku kankei (Shōwa 20-nen 9-gatsu 3-ka, Shigemitsu Gaimudaijin to Makkāsā kaiken kankei ari)] [Ref. B17070000700]).

Thus, all 100,000 posters with the text of the proclamations that had been distributed to Occupation Forces around the country were incinerated and were never seen by the public. However, military scrip denoted in marks was already being used in occupied Germany, and the situation was such that one could not be optimistic about direct military government in Japan, too. The swift response by Foreign Minister Shigemitsu and the others, along with the fact that government functions were strong and stability of order was being maintained—as shown by Chief of Staff Sutherland marveling at the “miracle” that the disarming of Japanese forces was being carried out in an orderly fashion—caused the withdrawal of direct military government.

The Crisis at Tateyama, Chiba Prefecture

A similar incident occurred at Tateyama in Chiba Prefecture. On the morning of September 3, an occupation force with 3,000 troops led by Brigadier General Julian Cunningham landed at Tateyama. That afternoon, Cunningham visited Consul General Hayashi Yasushi and handed over a document listing his demands. This document said one of the purposes of the occupation was “to supervise civilian administration within the objective area.” It stated that a Military Government Staff Section charged with this responsibility would have jurisdiction over the courts of law, police, administration of finance, education, transportation, and so forth. It also directed effective immediately that all schools and bars be closed, a curfew be imposed on going out at night, and that not more than ten people may assemble in public.

Having received the report from Consul General Hayashi, the Yokohama Liaison Office, feeling “serious anxieties” about direct military government, immediately dispatched a memorandum to the General Headquarters in order to confirm its real intentions. This was because the Yokohama Liaison Office for its part had understood military government of the Occupation Forces was founded on “the functions of the Japanese Government . . . being maintained and respected.” Subsequently, this was chalked up to a “misunderstanding” between the Japanese side and the Occupation Forces, and the anxieties about direct military government dissipated (see, for example, “From Yokohama Liaison Office to SCAP GHQ, Memorandum,” in Item: “4. The matters related to stationing of U.S. Army in various districts (excluding Atsugi and Yokohama) -including situation and movement report of Allied Forces- from September, 1945 / (3) The matters related to stationing of troops in Kanto District (excluding Atsugi and Yokohama)” [4. Kakuchiku (Atsugi, Yokohama o nozoku) ni okeru Beigun no shinchū kankei: Rengōgun no jōkyō, dosei hōkoku o fukumu, Shōwa 20-nen 9-gatsu/ (3) Kantō chiku shinchū kankei (jō Atsugi, Yokohama)] (Ref. B18090046300); and also “Chiba Prefecture Telephone Report, September 7: Item Regarding the Demands of the US Forces,” in Item: “4. Military Administration in General / 1) Implementation in general (including the orders issued by U.S. military personnel) / Partition 1” [4. Gunsei ippan / 1) Jisshi ippan (Beigunjin meiri o fukumu)]; Ref. B17070003400, images 33–35]).

From “Military Government” to “Civil Affairs”

In July 1949, the Eighth Army headquarters redesignated most of its “military government” organizations as “civil affairs” units (see Image 10). For example, the Military Government Section became the Civil Affairs Section, while the regional Military Government teams became regional Civil Affairs teams in Civil Affairs Regions. Furthermore, large-scale downsizing of these organizations was also carried out. The Japanese side viewed this “as an expression of the idea that gradually responsibility is going to be transferred to the Japanese government” (Item: “4. Military Administration in General / 2) Transfer of military administration to civil administration” [4. Gunsei ippan /2) Gunsei o minsei ni ikan kankei] [Ref. B17070003600]). The tide was beginning to turn for occupation policy as well.

[Image 10] Item: “4. Military Administration in General / 2) Transfer of military administration to civil administration” [4. Gunsei ippan /2) Gunsei o minsei ni ikan kankei] (Ref. B17070003600, image 2)

III. Records on End-of-War Liaison Work

The Cessation of Diplomatic Rights

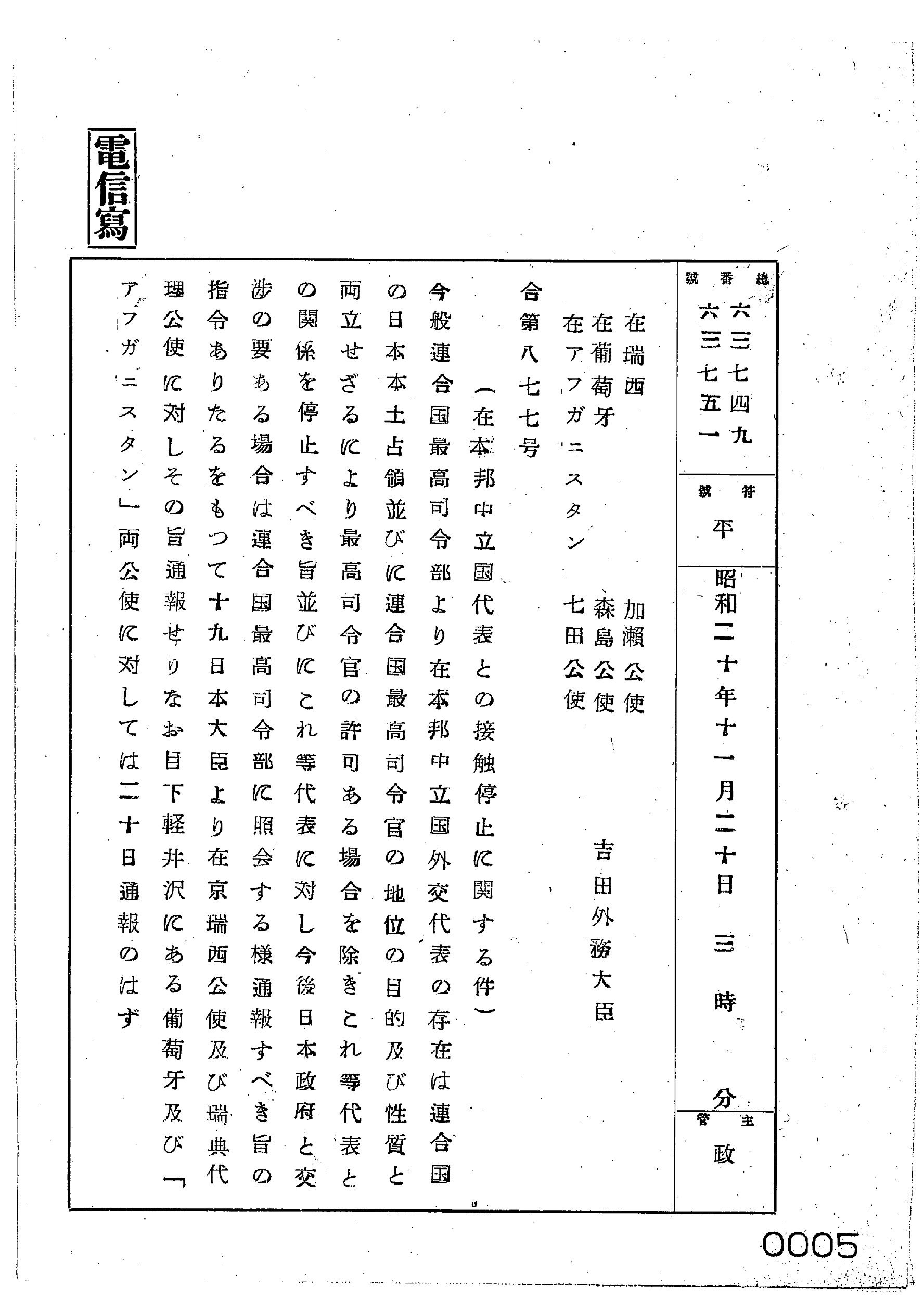

At the time of Japan’s surrender, through the Swiss government the US demanded that assets and official documents of Japan’s diplomatic mission in six neutral countries be handed over to the Allied powers. On August 16, Foreign Minister Tōgō Shigenori directed Ambassador to Switerzland Kase Toshikazu to reject these demands on the grounds that they did not come under any of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. However, the Allied powers turned a deaf ear, and in early November all contact and communications with foreign governments was forbidden (see Image 11). Diplomacy in the sense of handling external relations ceased to be, and Japan entered an era in which parleying with the Occupation Forces was the whole of its “diplomacy” (see, for example, File: “The stoppage of Japanese diplomatic rights by the demise of the Pacific War and the background till their restoration (compiled with duplicate documents)” [Taiheiyō sensō shūketsu ni yoru Honpō gaikōken no teishi oyobi kaifuku ni itaru kei’i (shabunsho de henshū)] [Ref. B17070076100]).

[Image 11] Item: “1. The stoppage of Japanese diplomatic rights by the demise of the Pacific War from November, 1945 / 1) The stoppage of contact with representative of neutral country in Japan from November, 1945” [1. Taiheiyō sensō shūketsu in yoru Honpō gaikōken no teishi kankei, ji Shōwa 20-nen 11-gatsu /1) Zai-Honpō chūrikkoku daihyō to no sesshoku teishi kankei, ji Shōwa 20-nen 11-gatsu] (Ref. B17070076600, image 2). The image here is a copy of a telegram from Foreign Yoshida Shigeru telling Japanese envoys to cease contacts.

The Establishment of Liaison Organizations

On August 22, Japan established the War Termination Processing Conference and the War Termination Liaison Committee as liaison organization for handling the war’s termination. The former was a conference comprising the prime minister and other key Cabinet members, while the latter was centered on the Chief Cabinet Secretary and comprised officials from each of the ministries. With the establishment on August 26 of the War Termination Central Liaison Office (WTCLO) as an external bureau of MOFA, both of these bodies were abolished.

However, as the importance of WTCLO—which was responsible for parleying with the Allied powers—increased, questions were raised within government circles about whether it was appropriate or not for a mere external bureau of MOFA to engage in direct talks with GHQ as a representative of the Japanese government, leading to the matter of reorganizing the WTCLO. The then-Cabinet of Prince Higashikuni on September 8 presented MOFA with an “expansion and reorganization proposal” that would separate these liaison organizations from MOFA and place them directly under the Cabinet. MOFA was against the proposal, arguing that the enormous organization to the contrary would hinder efficiency, and that the liaison organization should be retained through and through as an external MOFA bureau. Foreign Minister Shigemitsu Mamoru was strongly opposed to the Cabinet’s proposal, arguing for the “unification of diplomacy (external negotiations),” and resigned his post on September 17.

The WTCLO reorganization issue was settled by having it remain an external bureau of MOFA as it had been. A major organizational change was then carried out to strengthen liaising and coordination with other ministries, with the WTCLO leadership comprising a two-person team of director and deputy-director (see “Revised War Termination Central Liaison Office Executive Structure” [Kaisei shūsen renraku jimukyoku kansei], in Item: “End-of-War Administration information / No. 1” [Shūsen jimu jōhō / Dai-1-gō] [Ref. B17070009000, image 2]). Also, a War Termination Liaison Committee was established in each ministry to strengthen communications among the ministries. These committees met nearly every day, and the minutes of those meetings from October 1945 to July 1948 remain available (see File: “Termination-of-the-war liaison ministries committee meeting minutes / Vol. 1” [Shūsen renraku kakushō iinkai gijiroku, Dai-1-kan] [B18090106500]). We can see from a glance at the minutes that they discussed a wide range of issues, including economic controls, procuring goods, foodstuffs, transportation, and purge issues.

Local liaison offices were established under the WTCLO in the major areas where US forces were stationed, including Yokohama, Kyoto, Osaka, and Fukuoka, and there they handled liaising with the local military government teams. In 1948, the WTCLO became the Central Liaison and Coordination Bureau (CLCB) under the Prime Minister’s Agency, but with the administrative reforms of 1949 it was once again placed under MOFA’s Liaison Office. The records from after the 1948 reorganization as the CLCB are contained in such files as “A matter related to the Central liaison council / Meeting minutes Vol. 1 / 1st – 50th” [Chūo renraku kyōgikai kankei ikken / Gijiroku kankei, Dai-1-kan, Dai-10-kai ~ Dai-50-kai” (Ref. B18090110300) and “Central liaison committee managers meeting minutes / Vol. 1” [Renraku chōsei chūō iinkai kanjikai gijiroku, Dai-1-kan] (Ref. B18090104200). The meeting minutes are of particularly deep interest.

Also, when it comes to parleys with the Occupation Forces and liaison work in the early years, the “Reference on Liaison Work (Semi-Final Draft)” [Renraku gyōmu no sankō (jun-ketteian)] (in Item: “7. Liaison service with the General Headquarters [Sōshireibu to no renraku gyōmu kankei] [Ref. B17070011000, images 3–22]) prepared by the First Demobilization Bureau is instructive.

(to be continued in the next installment)

[1] Japanese public documents and other records that are important as historical materials connected to relations between Japan and neighboring Asian countries, etc., from modern and contemporary periods.

[2] Nihon gaikō bunsho [Documents on Japanese Foreign Policy] from the postwar period are as follows. (As of December 2024).

Reparations Negotiations Following the Conclusion of the San Francisco Peace Treaty Part 2. 1 volume.

Reparations Negotiations Following the Conclusion of the San Francisco Peace Treaty Part 1. 1 volume.

Reversion of Okinawa, Vol. 1 [covers period from the Third Yoshida Cabinet to the Ikeda Cabinet]. 1 volume.

Japan’s Accession to GATT, Vols. 1–2. 2 volumes.

Showa Era, Series IV, Japan-U.S. Relations, Vol. 1-1, and Vol. 1-2 (1952–1954). 1 volume.

Treaty of Peace between Japan and the Republic of China. 1 volume.

Japan’s Admission to the United Nations. 2 volumes.

The Era of Occupation, Special Studies. 1 volume.

The Era of Occuption, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2. 2 volumes

Treaty of Peace with Japan, Signing and Entry into Force. 1 volume.

Treaty of Peace with Japan, Negotiations with the United States. 1 volume.

Treaty of Peace with Japan, Preparatory Work. 1 volume.

Records related to the conclusion of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, Vol. 5.

Records related to the conclusion of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, Vol. 1.

Records related to the conclusion of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, Vol. 2.

Records related to the conclusion of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, Vol. 3.

Records related to the conclusion of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, Vol. 4.