JACAR Newsletter

JACAR Newsletter Number 44

July 30, 2024

Special Feature (2)

Commemorating the 60th Anniversary of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics: Insights from the JACAR Database

1. Introduction

The Olympics are currently underway in Paris, France (as of July 30, 2024), and I suppose many readers are busy keeping tabs on the action. The Games are adding a bolt of excitement to the year 2024, which also marks the sixtieth anniversary of the Games of the XVIII Olympiad—the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

The Tokyo Olympics in 1964 were not only the first Games to take place in Japan; they were the first for Asia as a whole. Running through the 1964 Olympics was a current of symbolism: of Japan’s postwar recovery, of Japan’s return to the global community under the Treaty of San Francisco and as a member of the United Nations, and of the country’s dazzling economic boom.

A closer look at the 1964 Olympics also reveals elements of continuity with the 1940 Olympics, which Tokyo won the bid for but ultimately forfeited amid the intensifying the Second Sino-Japanese War. Those common threads between the 1964 Games and the 1940 “Games that never were,” as the saying goes in Japan, are particularly evident in plans for competition venues and other areas.

To help commemorate the 60th anniversary of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, this special feature draws on JACAR resources to explore the historical trajectory stretching from the bidding for and the forfeiture of the 1940 Olympics to the holding of the 1964 Olympics—the “two Tokyo Olympics”—with an emphasis on the element of place.

2. Japan’s Successful Bid for—and Forfeiture of—the 1940 Tokyo Olympics

The idea of bringing the Olympics to Japan came to the fore in the 1930s when NAGATA Hidejirō, then mayor of Tokyo City, spearheaded a bid to host the Games of the XII Olympiad in Tokyo City.

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 2/ Division-1,”

image 2, Ref. B04012505500

According to these materials (Image 2), NAGATA stated that the 1940 Olympics (the 12th Olympic Games) “happen to coincide perfectly with the 2,600th anniversary of Japan’s founding, which would make hosting the Games a tremendous commemoration of the country’s history.” Essentially, the mayor was calling for Tokyo City to enter the running for the Olympics as a project that would symbolize Japan’s “national polity” in celebrating 2,600 years since the founding of the imperial line. The documents make the case by presenting several objectives, including “benefits for our national physical education” and “fostering a better understanding of Japan among foreign peoples,” along with reasons such as the solid progress that the Tokyo area was continuing to make in the recovery from the Great Kantō Earthquake.

NAGATA and his fellow proponents eventually saw their drive come to fruition: in July 1936, the general assembly of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) awarded the 12th Olympics to Tokyo. With that, the Organizing Committee for the 12th Olympic Games formed in Japan and set to work.

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 1/ Division-6,”

image 24, Ref. B04012505200

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 1/ Division-6,”

image 68, Ref. B04012505200

Historical documents offer a wealth of insights into how that process unfolded. A good place to start is the plan for the 1940 Tokyo Olympics that the organizing committee discussed.

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 1/ Division-6,”

image 27, Ref. B04012505200

The first item of business for the organizing committee was to discuss possible venues. After deciding that the facilities for the Games would be “simple and sturdy,” the group then came up with a long list of potential sites. Candidate locations for the stadium included Yoyogi, reclaimed land near Shinagawa Station, the Komazawa golf course, Kamitakaido, Suginami, Iogi, Kinutadai, Saginomiya, and Jingū Gaien, all of which the committee compared and assessed in terms of area, distance from major areas, and transportation conditions.

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 1/ Division-1,”

image 31, Ref. B04012504700

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 1/ Division-1,”

image 66, Ref. B04012504700

After doing a survey of potential sites for Olympic competitions, the venue examiners named Yoyogi as the top candidate in a report dated January 20, 1937. Among the Yoyogi proposal’s biggest backers was KISHIDA Hideto, who served as an examiner.

Yoyogi was home to the Japanese army’s “Yoyogi Military Parade Ground,” a space that the Imperial Guard and units of the 1st Division used for training purposes. Recognizing the enormous amount of land the location could offer, the venue examiners formulated a plan to turn the parade ground into a massive stadium capable of accommodating 100,000 spectators.

(From the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan’s Map/Aerial Photograph Viewing Service <https://mapps.gsi.go.jp/>)

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 1/ Division-3,”

image 35, Ref. B04012504900

One of the more interesting materials available is a written petition from a meeting of the leaders of all the town councils in Shibuya Ward. Given that the Olympics were to “commemorate the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of the imperial line,” the signatories to the document “graciously petition for” the building of the stadium on the “Yoyogi Military Parade Ground, which surrounds the sacred precinct of the Meiji Shrine.”

However, the process of selecting a main site would soon run into a major complication: the military refused to approve the construction of the Olympic stadium on the Yoyogi Military Parade Ground, which had emerged as the first proposal. Looking for a feasible alternative, the organizing committee began to shift its focus to Jingū Gaien.

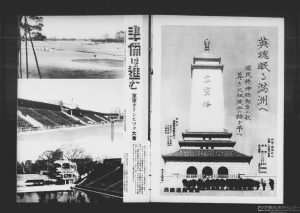

image 2, Ref. A06031060300

There was already a stadium in Jingū Gaien: the approximately 35,000-seat Meiji Jingū Gaien Stadium, which was designed by KOBAYASHI Masaichi (who also happened to be one of the venue examiners for the organizing committee) and completed in 1924. The committee thus drew up the Jingū Gaien proposal around the existing stadium, aiming to renovate the facility for Olympic use.

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 1/ Division-2,”

image 54, Ref. B04012504800

The organizing committee gave the director of the Ministry of the Interior’s Bureau of Shrine Affairs a formal request to renovate the Meiji Shrine area into a suitable athletic venue, but the Bureau of Shrine Affairs balked at the notion of turning it into a space with a capacity of 100,000. The Jingū Gaien proposal thus eventually ran aground, too.

Ultimately, the members of the organizing committee regrouped around a proposal to use the Komazawa golf course as the main Olympic location—only for the times to erode into full-fledged war. The Marco Polo Bridge Incident on July 7, 1937, a year before the Komazawa golf course proposal took shape, sparked the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Several months later, in January 1938, Prime Minister KONOE Fumimaro issued a statement declaring that it would “no longer negotiate with the Nationalist Government.” An end to the hostilities, therefore, was nowhere in sight. Calls for Tokyo to relinquish its Olympic Games began to mount, eventually prompting the cabinet to reach an official resolution to give up the competition on July 15, 1938.

image 5, Ref. B04012504200

A look at Ministry of Foreign Affairs documents on overseas coverage highlights the implications of the government’s decision. In the view of foreign media, virtually no country needed amicable relationships with foreign countries more than Japan did at the time. The country’s voluntary surrender of the Olympics sent citizens’ long-held dreams “up in smoke” and “demonstrated a division among the people.” According to the documents, foreign media were calling the forfeiture a “disastrous failure” “perpetrated by the Japanese military.”

Documents Relating to Hosting the Olympic Games in Japan: Vol. 5/ Division-2,”

image 58, Ref. B04012507100

In response to the forfeiture, the Tokyo City Olympic Committee issued an official statement. What had driven Tokyo’s Olympic bid to success with the support of experts and a tremendous effort, the statement reads, was the “prosperity of the Japanese Empire and the support of the whole nation.” Losing the opportunity to host Asia’s first Olympic Games was, in the committee’s words, “an unbearable disappointment.”

However, the statement went on to proclaim that the committee would “do everything in its power to bring the next Olympic Games to Tokyo City, firm in its belief that peace in the Orient is soon to come” and concluded with a “humble appeal for future support.”

The 1940 Tokyo Olympics thus became the “Games that never were.” The committee members’ statement brimmed with both dejection and hope for the future. Had the “tremendous effort” really all gone “up in smoke?” Delineating the answer to that question requires a closer examination of where the vision and plan for the 1940 Tokyo Olympics ultimately led.

3. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics: Postwar Japan and Another Olympic Bid

On October 21, 1943, the Meiji Jingū Gaien Stadium, one of the candidate venues for the 1940 Tokyo Olympics, was the site of a send-off rally for student soldiers. With stormy skies dumping rain on the gathering, the attendees listened to a speech by Prime Minister TŌJŌ Hideki before sending up chants of “Long live the Emperor!” Footage of the event, including shots of 25,000 students marching across the venue’s muddy grounds, is available in the Japan News archive.

After Japan’s defeat in 1945, the country came under GHQ occupation, and most military-related facilities were converted into accommodations for the stationed US military.

image 1, Ref. A17110906800

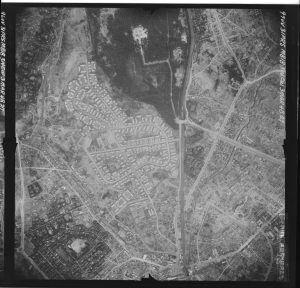

According to a 1946 outline (Image 14), the War Damage Reconstruction Board was responsible for constructing accommodations and facilities at the request of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. The Yoyogi Military Parade Ground, another leading candidate venue for the 1940 Tokyo Olympics, also underwent a conversion into housing for US forces in Japan.

(from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan’s Map/Aerial Photograph Viewing Service <https://mapps.gsi.go.jp/>)

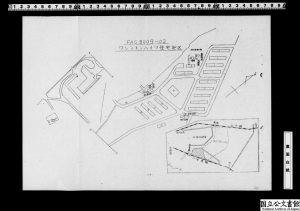

fuhyō no henkō ni kansuru bunsho dai 49 gō ni tuite

(Sōri-fu – Chōtatsu-chō),”

image 46, Ref. A22100392300

These documents (Images 15 and 16) show extensive rows of accommodations. The plot, named “Washington Heights,” housed American military personnel and their families, along with schools, churches, and other facilities.

In 1951, six years after Japan’s defeat in WWII, the Treaty of Peace with Japan was signed in San Francisco. Japan proceeded to regain its sovereignty in 1952.

image 2, Ref. A22100072800

The next documents to examine are records (Image 17) that the Ministry of Construction prepared and submitted for discussion to the meeting of vice-ministers in 1953, just after the restoration of Japan’s sovereignty.

What the “gathering area” in the documents’ title specifically signified is unknown, given the lack of any concrete explanation, but what we do know is that Yoyogi and Gaien were the top two candidate sites, in that order. The records comprise brief summaries of the current condition, topography, area, transportation conditions, and other characteristics of each site. The description of Yoyogi’s current condition says that the site is “the former Yoyogi Military Parade Ground, currently the housing complex for stationed forces and their families (Washington Heights),” with an accompanying estimate indicating that construction work would include compensation for relocation. By 1953, then, the government had identified Yoyogi and Jingū Gaien as suitable locations for “gathering” and begun preliminary work on building “areas” for that purpose.

On April 28, 1952, the Treaty of San Francisco came into effect, and one month later, Governor YASUI Seiichirō announced Tokyo’s bid for the Games of the XVII Olympiad (the 1960 Olympics).

image 1, Ref. A21100497100

While Tokyo went on to lose its bid for the 1960 Games to Rome, it would not have to wait long for good news. At the 1959 general assembly of the IOC, the members officially chose Tokyo to host the Games of the XVIII Olympiad—the 1964 Olympics.

image 1, Ref. A22101566800

After a 24-year wait, a span that included Japan’s defeat in WWII, the Tokyo Olympics were finally about to become a reality. The proposal for the Act on Special Measures Required for Preparation, etc. of the Tokyo Olympic Games (Image 19) laid out the nature of the work ahead, explaining that the government needed to “take special measures to ensure the smooth preparations for and operations of the Tokyo Olympic Games.”

image 1, Ref. A22100699700

The Sports Promotion Council submitted a request to Prime Minister KISHI Nobusuke for securing a facility site to prepare for the Tokyo Olympics. The petition mentions the area around Meiji Jingū Gaien as the optimal location for a sports complex, indicating the Council’s intentions. The government eventually decided to adopt the suggestion and build the main stadium for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics at Jingū Gaien, leading to the renovation of the existing Jingū Gaien Stadium and the construction of what is now known as the “former” National Stadium.

image 1, Ref. A24010120200

Meanwhile, Yoyogi—the Washington Heights area—emerged as a potential site for the Olympic Village and indoor stadium. The initial plan was to put the Olympic Village in Asaka (Saitama Prefecture), but that would eventually change. After extensive negotiations, the cabinet reached a decision in 1961 to receive the return of the Washington Heights land and construct the Olympic Village and indoor stadium there.

The US military accommodations in Washington Heights were repurposed for athlete housing, one unit of which remains standing in Yoyogi Park to this day, and the TANGE Kenzō-designed Yoyogi 1st Gymnasium (also known as the Yoyogi National Stadium) was completed in September 1964.

(photographed by the author, June 2024)

Jingū Gaien and Yoyogi, which had both been prominent prospects for the 1940 “Games that never were,” thus became the main venues for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics—a clear example of the sense of continuity linking 1940 and 1964.

Once all the preparations were complete, the 1964 Tokyo Olympics kicked off with the opening ceremony on October 10 at the former National Stadium. The honor of setting the Olympic flame alight went to SAKAI Yoshinori, a track and field athlete who was born in Hiroshima Prefecture on August 6, 1945—the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Writer MISHIMA Yukio, who covered the Olympics as a special correspondent for the Asahi Shimbun and two other newspapers, described the lighting as “the crystallization of the simple, unadorned vitality of Japan’s youth.”

Over the two-week period from October 10 to 24, a total of 5,152 athletes from 93 countries participated in 163 events in 20 sports. Tokyo also played host to the 13th International Stoke Mandeville Games (the predecessor of the Paralympics), which commenced on November 8 and welcomed 378 athletes from 21 countries.

The 1964 Tokyo Olympics were fixtures on TV and across the rest of the then-burgeoning media landscape, with outlets covering the showings of numerous athletes. Notable faces of the Games included the Japanese women’s volleyball team, known as the “Oriental Witches,” marathon runners Abebe Bikila (Ethiopia) and TSUBURAYA Kōkichi, and weightlifter MIYAKE Yoshinobu. TANGE Kenzō, the architect of the Yoyogi 1st Gymnasium, received an Olympic Diploma of Merit from the IOC in a triumph that helped solidify modern Japanese architecture’s standing on the global stage.

The 1964 Tokyo Olympics thus became an enduring symbol of Japan’s postwar identity: its return to the international community, post-war recovery, and rapid economic growth. A look at the “places” central to the festivities, however, reveals how the legacy of the 1940 Tokyo Olympics—the prewar “Games that never were”—shaped both the vision and plan for the 1964 Olympics.

4. Conclusion

The 2020 Tokyo Olympics were held in 2021, due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than half a century after the 1964 Games. “Recovery” was again a central theme of the project, with Japan still working to make its way back from the Great East Japan Earthquake, and the places at the core of the Games yet again included Jingū Gaien and Yoyogi. Evidently, we continue to inherit the legacy and memory of the original “Tokyo Olympics.”

As I noted earlier, the year 2024 marks 60 years since the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and also the year of the Paris Olympics and Paralympics. A wealth of materials related to not only past Tokyo Olympics but also Games in other countries are available to the public through the offerings of the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records, providing a wonderful opportunity for all of us to explore and reflect on the history of the Olympics and Paralympics.

Note: Some names and other expressions in quotes have been revised for clarity.

Bibliography

-

- “Tōkyō Orinpikku, 1940-nen –– Maboroshi no Orinpikku he ––” [The Tokyo Olympics, 1940 –– to the “Games that never were”], (JACAR, “Shitte naruhodo Meiji, Taishō, Shōwa no seikatsu to bunka,” https://www.jacar.go.jp/seikatsu-bunka/p06.html)

- IRIE, Akira, and ARUGA Tadashi, eds. Senkanki no Nippon gaikō [Japan’s interwar diplomacy]. Tokyo: Tokyo University Press, 1984.

- FURUKAWA, Takahisa. Kōki, Banpaku, Orinpikku: Kōshitsu burando to keizai hatten [The Imperial era, the Expo, and the Olympics: The imperial family and economic development]. Tokyo: Chūōkōron-Sha, 1998.

- OIKAWA Yoshinobu, ed. Tōkyō Orinpikku no shakaikeizai-shi [A socioeconomic history of the Tokyo Olympics]. Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyouronsha, 2009.

- KATAKI Atsushi. Orinpikku shitī, Tōkyō, 1940, 1964 [The Olympic city: Tokyo, 1940 and 1964]. Tokyo: Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2010.

- TOYOKAWA, Saikaku. Tange Kenzō: Sengo Nihon no kōsōsha [Tange Kenzō: Conceptualizer of postwar Japan]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2016.

- HAMADA, Sachie. Tōkyō Orinpikku no tanjō: 1940 nen kara 2020 nen e [The birth of the Tokyo Olympics: From 1940 to 2020]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2018.

- FURUKAWA, Takahisa. Kenkoku shinwa no shakai-shi: Shijitsu to kyogi no kyōkai [A social history of the birth-myth of the nation: The boundary between historical fact and fiction]. Tokyo: Chūōkōron-Shinsha, 2020.

KATO Souichiro, Assistant Researcher, Japan Center for Asian Historical Records